Last week, we looked at how Sun Belt teams fared in terms of yards per play. This week, we turn our attention to how the season played out in terms of the Adjusted Pythagorean Record, or APR. For an in-depth look at APR, click here. If you didn’t feel like clicking, here is the Reader’s Digest version. APR looks at how well a team scores and prevents touchdowns. Non-offensive touchdowns, field goals, extra points, and safeties are excluded. The ratio of offensive touchdowns to touchdowns allowed is converted into a winning percentage. Pretty simple actually.

Once again, here are the 2017 Sun Belt standings.

And here are the APR standings with conference rank in offensive touchdowns, touchdowns allowed, and APR in parentheses. This includes conference games only.

Finally, Sun Belt teams are sorted by the difference between their actual number of wins and their expected number of wins according to APR.

Georgia State was the lone Sun Belt team that saw their actual record differ significantly from their APR. In eight conference games, the Panthers allowed five more touchdowns than they scored and were outscored by 28 points overall in conference play. However, the Panthers scored at the right times, finishing 4-0 in one-score conference games. Their five league wins all came by ten points or fewer while each league loss came by at least two touchdowns. That’s quite a tightrope to walk and I have my doubts as to whether they can keep their balance for much longer.

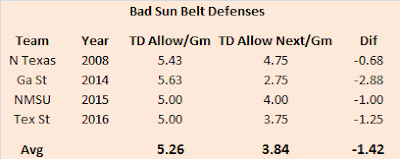

Louisiana-Monroe finished with a losing record for the fourth consecutive season, but the Warhawks played an entertaining brand of football in 2017. They scored the most touchdowns in Sun Belt play, averaging five per contest, but also allowed the most, permitting 5.63 per game. Offensively, they were one of the best Sun Belt teams since I have been tracking APR data (2005). Conversely, they were also one of the worst Sun Belt defenses in that same span. It stands to reason then that a small improvement on defense or a small decline on offense could have a profound impact on the Warhawks in 2018. But which is more likely? Do strong Sun Belt offenses remain that way or do they regress? Do bad Sun Belt defenses stay bad or do they show improvement the next season? To find out, I looked at all Sun Belt offenses that averaged at least five touchdowns per conference game since 2005 and how they performed the following season. I then did the same thing for Sun Belt defenses that allowed at least five touchdowns per conference game. Let’s get to the results, starting with the great offenses.

As expected, these great offenses declined in the aggregate. However, one team managed to improve and the average decline of about two thirds of a touchdown per game still left these teams in great shape offensively. For perspective, that average of 4.56 offensive touchdowns per game would have ranked fourth in the Sun Belt in 2017. What about those bad defenses?

Once again, as expected, those extreme performances were not repeated. Every bad defense improved the following season, and three improved by at least one touchdown per game. I know this is an extremely small sample size, but I would be cautiously optimistic about 2018 were I a Warhawk fan. Matt Viator will be entering his third season in charge, a year when teams often improve. In addition, the offense is likely to remain one of the best in the Sun Belt while the defense is likely to improve upon their horrific

performance in 2017. A conference title might be too ambitious, but a return to the postseason is certainly on the table.

Well, that concludes our conference by conference dive into the 2017 season. Unfortunately, we still have 13 more weeks until the first Thursday night action of 2018. Between now and then, expect to see a few posts on polls, a Vegas gambling recap, and an Adjusted Pythagorean look at the NFL. I don't have a specific schedule laid out, but check back once a week or so if you are dying for some Statistically Speaking content. As always, thanks for reading.

I use many stats. I use many stats. Let me tell you, you have stats that are far worse than the ones that I use. I use many stats.

Thursday, May 31, 2018

Thursday, May 24, 2018

2017 Yards Per Play: Sun Belt

Hard to believe, but we have reached the final conference in our offseason sojourn. Here are the 2017 Sun Belt standings.

So we know what each team achieved, but how did they perform? To answer that, here are the Yards Per Play (YPP), Yards Per Play Allowed (YPA) and Net Yards Per Play (Net) numbers for each Sun Belt team. This includes conference play only. The teams are sorted by Net YPP with conference rank in parentheses.

College football teams play either eight or nine conference games. Consequently, their record in such a small sample may not be indicative of their quality of play. A few fortuitous bounces here or there can be the difference between another ho-hum campaign or a special season. Randomness and other factors outside of our perception play a role in determining the standings. It would be fantastic if college football teams played 100 or even 1000 games. Then we could have a better idea about which teams were really the best. Alas, players would miss too much class time, their bodies would be battered beyond recognition, and I would never leave the couch. As it is, we have to make do with the handful of games teams do play. In those games, we can learn a lot from a team’s YPP. Since 2005, I have collected YPP data for every conference. I use conference games only because teams play such divergent non-conference schedules and the teams within a conference tend to be of similar quality. By running a regression analysis between a team’s Net YPP (the difference between their Yards Per Play and Yards Per Play Allowed) and their conference winning percentage, we can see if Net YPP is a decent predictor of a team’s record. Spoiler alert. It is. For the statistically inclined, the correlation coefficient between a team’s Net YPP in conference play and their conference record is around .66. Since Net YPP is a solid predictor of a team’s conference record, we can use it to identify which teams had a significant disparity between their conference record as predicted by Net YPP and their actual conference record. I used a difference of .200 between predicted and actual winning percentage as the threshold for ‘significant’. Why .200? It is a little arbitrary, but .200 corresponds to a difference of 1.6 games over an eight game conference schedule and 1.8 games over a nine game one. Over or under-performing by more than a game and a half in a small sample seems significant to me. In the 2017 season, which teams in the Sun Belt met this threshold? Here are Sun Belt teams sorted by performance over what would be expected from their Net YPP numbers.

Coastal Carolina was the lone Sun Belt team that saw their actual record differ significantly from their expected record. The Chanticleers first season as an FBS program was a unique one. It began in the summer when head coach Joe Moglia went out on medical leave. It continued once the season began when Coastal lost to zombie program UAB and FCS Western Illinois before nearly beating Arkansas later in the year. The Chanticleers actually began life in the Sun Belt 0-6 before winning their final two games and sowing some seeds of optimism heading into 2018. The Chanticleers were a little unlucky in close games, finishing 1-3 in one-score Sun Belt contests (1-5 overall with close losses to UAB and Arkansas). However, they were also done in by their inability to cover kick offs. Coastal allowed four kick return touchdowns in 2017 and allowed five more non-offensive touchdowns than they scored in Sun Belt play. Those kickoff returns (and a well-time fumble return) provided the margin of defeat in their games against Louisiana-Monroe and Georgia State.

In other news regarding FBS novices, South Alabama will have a new football coach in 2018. Joey Jones guided the South Alabama program since its inception and this is not intended as a slight, but the Jaguars were a very anonymous team under his watch. If you aren’t a regular mid-week Fun Belt viewer or an alum of USA, you may not even know that South Alabama is an FBS program. It doesn’t help that the Jaguars have not really distinguished themselves as either a very bad or very good mid-major program. In their six seasons as members of the Sun Belt, the Jaguars have finished with either five or six wins four times. They went 2-11 in their first season and 4-8 this past year, but otherwise they have hovered around the six win mark. However, one group that will certainly recognize South Alabama are degenerate gamblers as the Jaguars have pulled off several massive upsets in their brief history.

In the College Football Playoff era (beginning with 2014), South Alabama has pulled five outright upsets as a double-digit underdog. This is tied for the second most double-digit upsets in that span and tied for the most among mid-major teams. The Jaguars have also spread their upsets around, pulling at least one in three of the four seasons of the CFP era. Joey Jones never brought the Jaguars a Sun Belt title, but he took them to two bowl games and guided them to quite a few colossal upsets.

So we know what each team achieved, but how did they perform? To answer that, here are the Yards Per Play (YPP), Yards Per Play Allowed (YPA) and Net Yards Per Play (Net) numbers for each Sun Belt team. This includes conference play only. The teams are sorted by Net YPP with conference rank in parentheses.

College football teams play either eight or nine conference games. Consequently, their record in such a small sample may not be indicative of their quality of play. A few fortuitous bounces here or there can be the difference between another ho-hum campaign or a special season. Randomness and other factors outside of our perception play a role in determining the standings. It would be fantastic if college football teams played 100 or even 1000 games. Then we could have a better idea about which teams were really the best. Alas, players would miss too much class time, their bodies would be battered beyond recognition, and I would never leave the couch. As it is, we have to make do with the handful of games teams do play. In those games, we can learn a lot from a team’s YPP. Since 2005, I have collected YPP data for every conference. I use conference games only because teams play such divergent non-conference schedules and the teams within a conference tend to be of similar quality. By running a regression analysis between a team’s Net YPP (the difference between their Yards Per Play and Yards Per Play Allowed) and their conference winning percentage, we can see if Net YPP is a decent predictor of a team’s record. Spoiler alert. It is. For the statistically inclined, the correlation coefficient between a team’s Net YPP in conference play and their conference record is around .66. Since Net YPP is a solid predictor of a team’s conference record, we can use it to identify which teams had a significant disparity between their conference record as predicted by Net YPP and their actual conference record. I used a difference of .200 between predicted and actual winning percentage as the threshold for ‘significant’. Why .200? It is a little arbitrary, but .200 corresponds to a difference of 1.6 games over an eight game conference schedule and 1.8 games over a nine game one. Over or under-performing by more than a game and a half in a small sample seems significant to me. In the 2017 season, which teams in the Sun Belt met this threshold? Here are Sun Belt teams sorted by performance over what would be expected from their Net YPP numbers.

Coastal Carolina was the lone Sun Belt team that saw their actual record differ significantly from their expected record. The Chanticleers first season as an FBS program was a unique one. It began in the summer when head coach Joe Moglia went out on medical leave. It continued once the season began when Coastal lost to zombie program UAB and FCS Western Illinois before nearly beating Arkansas later in the year. The Chanticleers actually began life in the Sun Belt 0-6 before winning their final two games and sowing some seeds of optimism heading into 2018. The Chanticleers were a little unlucky in close games, finishing 1-3 in one-score Sun Belt contests (1-5 overall with close losses to UAB and Arkansas). However, they were also done in by their inability to cover kick offs. Coastal allowed four kick return touchdowns in 2017 and allowed five more non-offensive touchdowns than they scored in Sun Belt play. Those kickoff returns (and a well-time fumble return) provided the margin of defeat in their games against Louisiana-Monroe and Georgia State.

In other news regarding FBS novices, South Alabama will have a new football coach in 2018. Joey Jones guided the South Alabama program since its inception and this is not intended as a slight, but the Jaguars were a very anonymous team under his watch. If you aren’t a regular mid-week Fun Belt viewer or an alum of USA, you may not even know that South Alabama is an FBS program. It doesn’t help that the Jaguars have not really distinguished themselves as either a very bad or very good mid-major program. In their six seasons as members of the Sun Belt, the Jaguars have finished with either five or six wins four times. They went 2-11 in their first season and 4-8 this past year, but otherwise they have hovered around the six win mark. However, one group that will certainly recognize South Alabama are degenerate gamblers as the Jaguars have pulled off several massive upsets in their brief history.

In the College Football Playoff era (beginning with 2014), South Alabama has pulled five outright upsets as a double-digit underdog. This is tied for the second most double-digit upsets in that span and tied for the most among mid-major teams. The Jaguars have also spread their upsets around, pulling at least one in three of the four seasons of the CFP era. Joey Jones never brought the Jaguars a Sun Belt title, but he took them to two bowl games and guided them to quite a few colossal upsets.

Thursday, May 17, 2018

2017 Adjusted Pythagorean Record: SEC

Last week, we looked at how SEC teams fared in terms of yards per play. This week, we turn our attention to how the season played out in terms of the Adjusted Pythagorean Record, or APR. For an in-depth look at APR, click here. If you didn’t feel like clicking, here is the Reader’s Digest version. APR looks at how well a team scores and prevents touchdowns. Non-offensive touchdowns, field goals, extra points, and safeties are excluded. The ratio of offensive touchdowns to touchdowns allowed is converted into a winning percentage. Pretty simple actually.

Once again, here are the 2017 SEC standings.

And here are the APR standings sorted by division with conference rank in offensive touchdowns, touchdowns allowed, and APR in parentheses. This includes conference games only, with the championship game excluded.

Finally, SEC teams are sorted by the difference between their actual number of wins and their expected number of wins according to APR.

As with YPP, no SEC team saw their APR differ significantly from their actual record although Texas A&M came close. The Aggies finished 4-1 in one-score conference games, with their quartet of victories coming by 23 total points. Outside of their ‘close’ loss to Alabama (when they cut the deficit to eight with seconds remaining), their other three conference defeats all came by at least two touchdowns.

Back around Columbus Day, you probably could have gotten decent odds that Barry Odom would not be coaching Missouri in 2018. After an uninspiring 4-8 debut, the Tigers were 1-4 in his second season with their lone win against an FCS opponent. Overall, the Tigers had three victories against FBS teams and just two conference wins under Odom’s guidance. The Tigers would lose their next game against Georgia, although they were somewhat competitive against the eventual national runners up, scoring 28 points against a stout Georgia defense. Following that defeat to the Dogs, Missouri would not lose again (in the regular season), pulverizing their last six foes by an average of 30 points per game! Their regular season finale against Arkansas was close, but the other five wins all came by at least four touchdowns. So Missouri is naturally an SEC East darkhorse heading into 2018 right? As the esteemed Lee Corso might say: Not so fast, my friend.

Missouri was quite dominant in their last six games of 2017, but let’s pause and consider the quality of opponent. The Tigers won non-conference games against Idaho and Connecticut, two teams that combined for seven wins in 2017. In addition, the four conference opponents the Tigers slaughtered did not sniff the postseason. Arkansas, Florida, Tennessee, and Vanderbilt combined for a 5-27 SEC record with three of the wins coming against each other (Florida and Vanderbilt over Tennessee and Florida over Vanderbilt). Outside of Arkansas, the Tigers did not struggle to put these teams away, but this is about as easy a closing slate as you could ask for in the rugged SEC. Contrast this with Missouri’s five-game losing streak. That quintet of teams all qualified for the postseason, with Auburn and Georgia winning their respective divisions. South Carolina won eight regular season games and both Kentucky and Purdue eked out bowl eligibility. If you change the sequencing by swapping say Tennessee with Georgia or Idaho with South Carolina, the narrative of a hot finish is not nearly as strong.

Even if the narrative is not completely accurate, Missouri still accomplished something pretty amazing. How many other teams have closed with six straight wins after a 1-5 start? By my count, only one.

Rutgers opened the 2008 season looking for their fourth consecutive bowl bid. The once moribund program was now a force to be reckoned with in college football (sort of). Alas, the Knights began the season 0-3, managing only 40 combined points in losses to Fresno State, North Carolina, and Navy. Rutgers pummeled an FCS school in their fourth games, but lost their next two to West Virginia and Cincinnati respectively. Rutgers held on to beat Connecticut in an ugly 12-10 crapfest, but bowl eligibility seemed out of reach. Discounting the 38 points they scored against Morgan State, Rutgers had averaged just over 13 points per game in their first six FBS contests. Then they flipped the proverbial switch. After edging Connecticut, the Knights won their last five games with ease. The offense put at least 30 points on the board in each game and Rutgers won those five contests by an average of 29 points per game! Unlike Missouri, the Knights also managed to win their bowl game, turning a 1-5 start into an 8-5 finish and third consecutive bowl win.

Despite some key offensive losses (a senior quarterback and a pair of NFL caliber receivers), in a transitional Big East, Rutgers got some preseason love in 2009. In his Norman Mailer sized preview magazine, Phil Steele even predicted a conference championship for the Knights. Record-wise, Rutgers improved in 2009, winning eight regular season games (and getting to nine with their bowl victory), but their schedule was very soft. They beat a pair of FCS teams, Florida International, and Army for half of their regular season victories. In Big East play, they managed just a 3-4 mark and were never in contention for the league title. In a more formidable SEC, Missouri will have the luxury of tempered expectations. The Tigers do bring back a talented quarterback, but lose their offensive coordinator as well as their leading rusher and receiver. Derek Dooley was brought in to be the new offensive coordinator and his hire does not inspire the utmost confidence. 2017 was the worst season for both Florida and Tennessee in a generation, so the window for a real breakthrough under Barry Odom could be slamming shut. Betdsi currently has Missouri’s over/under win total at 6.5. On the surface, this seems low considering how the Tigers finished the 2017 season, but upon further examination of the schedule and the dearth of quality teams the Tigers faced after mid-October plus the fact that Florida and Tennessee (and even Vanderbilt) are unlikely to be as bad as they were in 2016, this number seems right on the money.

Once again, here are the 2017 SEC standings.

And here are the APR standings sorted by division with conference rank in offensive touchdowns, touchdowns allowed, and APR in parentheses. This includes conference games only, with the championship game excluded.

Finally, SEC teams are sorted by the difference between their actual number of wins and their expected number of wins according to APR.

As with YPP, no SEC team saw their APR differ significantly from their actual record although Texas A&M came close. The Aggies finished 4-1 in one-score conference games, with their quartet of victories coming by 23 total points. Outside of their ‘close’ loss to Alabama (when they cut the deficit to eight with seconds remaining), their other three conference defeats all came by at least two touchdowns.

Back around Columbus Day, you probably could have gotten decent odds that Barry Odom would not be coaching Missouri in 2018. After an uninspiring 4-8 debut, the Tigers were 1-4 in his second season with their lone win against an FCS opponent. Overall, the Tigers had three victories against FBS teams and just two conference wins under Odom’s guidance. The Tigers would lose their next game against Georgia, although they were somewhat competitive against the eventual national runners up, scoring 28 points against a stout Georgia defense. Following that defeat to the Dogs, Missouri would not lose again (in the regular season), pulverizing their last six foes by an average of 30 points per game! Their regular season finale against Arkansas was close, but the other five wins all came by at least four touchdowns. So Missouri is naturally an SEC East darkhorse heading into 2018 right? As the esteemed Lee Corso might say: Not so fast, my friend.

Missouri was quite dominant in their last six games of 2017, but let’s pause and consider the quality of opponent. The Tigers won non-conference games against Idaho and Connecticut, two teams that combined for seven wins in 2017. In addition, the four conference opponents the Tigers slaughtered did not sniff the postseason. Arkansas, Florida, Tennessee, and Vanderbilt combined for a 5-27 SEC record with three of the wins coming against each other (Florida and Vanderbilt over Tennessee and Florida over Vanderbilt). Outside of Arkansas, the Tigers did not struggle to put these teams away, but this is about as easy a closing slate as you could ask for in the rugged SEC. Contrast this with Missouri’s five-game losing streak. That quintet of teams all qualified for the postseason, with Auburn and Georgia winning their respective divisions. South Carolina won eight regular season games and both Kentucky and Purdue eked out bowl eligibility. If you change the sequencing by swapping say Tennessee with Georgia or Idaho with South Carolina, the narrative of a hot finish is not nearly as strong.

Even if the narrative is not completely accurate, Missouri still accomplished something pretty amazing. How many other teams have closed with six straight wins after a 1-5 start? By my count, only one.

Rutgers opened the 2008 season looking for their fourth consecutive bowl bid. The once moribund program was now a force to be reckoned with in college football (sort of). Alas, the Knights began the season 0-3, managing only 40 combined points in losses to Fresno State, North Carolina, and Navy. Rutgers pummeled an FCS school in their fourth games, but lost their next two to West Virginia and Cincinnati respectively. Rutgers held on to beat Connecticut in an ugly 12-10 crapfest, but bowl eligibility seemed out of reach. Discounting the 38 points they scored against Morgan State, Rutgers had averaged just over 13 points per game in their first six FBS contests. Then they flipped the proverbial switch. After edging Connecticut, the Knights won their last five games with ease. The offense put at least 30 points on the board in each game and Rutgers won those five contests by an average of 29 points per game! Unlike Missouri, the Knights also managed to win their bowl game, turning a 1-5 start into an 8-5 finish and third consecutive bowl win.

Despite some key offensive losses (a senior quarterback and a pair of NFL caliber receivers), in a transitional Big East, Rutgers got some preseason love in 2009. In his Norman Mailer sized preview magazine, Phil Steele even predicted a conference championship for the Knights. Record-wise, Rutgers improved in 2009, winning eight regular season games (and getting to nine with their bowl victory), but their schedule was very soft. They beat a pair of FCS teams, Florida International, and Army for half of their regular season victories. In Big East play, they managed just a 3-4 mark and were never in contention for the league title. In a more formidable SEC, Missouri will have the luxury of tempered expectations. The Tigers do bring back a talented quarterback, but lose their offensive coordinator as well as their leading rusher and receiver. Derek Dooley was brought in to be the new offensive coordinator and his hire does not inspire the utmost confidence. 2017 was the worst season for both Florida and Tennessee in a generation, so the window for a real breakthrough under Barry Odom could be slamming shut. Betdsi currently has Missouri’s over/under win total at 6.5. On the surface, this seems low considering how the Tigers finished the 2017 season, but upon further examination of the schedule and the dearth of quality teams the Tigers faced after mid-October plus the fact that Florida and Tennessee (and even Vanderbilt) are unlikely to be as bad as they were in 2016, this number seems right on the money.

Thursday, May 10, 2018

2017 Yards Per Play: SEC

Eight conferences down, just two to go. This week we move cross country from the west coast to the southeast. Next up is the SEC. Here are the 2017 SEC standings.

So we know what each team achieved, but how did they perform? To answer that, here are the Yards Per Play (YPP), Yards Per Play Allowed (YPA) and Net Yards Per Play (Net) numbers for each SEC team. This includes conference play only, championship game excluded. The teams are sorted by division by Net YPP with conference rank in parentheses.

College football teams play either eight or nine conference games. Consequently, their record in such a small sample may not be indicative of their quality of play. A few fortuitous bounces here or there can be the difference between another ho-hum campaign or a special season. Randomness and other factors outside of our perception play a role in determining the standings. It would be fantastic if college football teams played 100 or even 1000 games. Then we could have a better idea about which teams were really the best. Alas, players would miss too much class time, their bodies would be battered beyond recognition, and I would never leave the couch. As it is, we have to make do with the handful of games teams do play. In those games, we can learn a lot from a team’s YPP. Since 2005, I have collected YPP data for every conference. I use conference games only because teams play such divergent non-conference schedules and the teams within a conference tend to be of similar quality. By running a regression analysis between a team’s Net YPP (the difference between their Yards Per Play and Yards Per Play Allowed) and their conference winning percentage, we can see if Net YPP is a decent predictor of a team’s record. Spoiler alert. It is. For the statistically inclined, the correlation coefficient between a team’s Net YPP in conference play and their conference record is around .66. Since Net YPP is a solid predictor of a team’s conference record, we can use it to identify which teams had a significant disparity between their conference record as predicted by Net YPP and their actual conference record. I used a difference of .200 between predicted and actual winning percentage as the threshold for ‘significant’. Why .200? It is a little arbitrary, but .200 corresponds to a difference of 1.6 games over an eight game conference schedule and 1.8 games over a nine game one. Over or under-performing by more than a game and a half in a small sample seems significant to me. In the 2017 season, which teams in the SEC met this threshold? Here are SEC teams sorted by performance over what would be expected from their Net YPP numbers.

No SEC teams significantly over or under-performed relative to their expected record based on YPP. The top three teams dominated the conference, finishing a combined 21-3 with Auburn’s loss to LSU the only one coming against the other eleven. There is really nothing interesting or new to report in that regard. So, instead I’ll focus on something that is rather interesting.

When Jim McElwain was relieved of his duties in late October, I realized no current coach in the SEC East at that point had ever won the division! In fact, the last three head coaches to win the division (McElwain, Pinkel, and Richt) had all departed within three seasons of winning the division! Is this standard practice in the SEC? To find out, I looked at all SEC coaches that have won division titles since the league expanded in 1992. I then calculated how many seasons they coached at their school after their most recent title. For example, Steve Spurrier won pretty much every SEC East title in the 90’s at Florida, but his most recent title with the Gators came in 2000. He coached just one additional season at Florida before resigning to become head coach of the Washington Redskins. Obviously, Spurrier was not forced out at Florida, but I still wanted to get an idea of how long each coach lasted after their last division title. I rounded partial seasons up, so Jim McElwain gets credit for one full season and Les Miles get credit for five even though they did not finish out their final campaigns. The following table lists the SEC division winning coaches who are no longer employed by the schools where they won titles. I have highlighted coaches who were removed for performance based reasons to differentiate those from coaches who moved on voluntarily. We can quibble with a few of those distinctions, but for the most part, I think they are accurate.

Those 17 head coaches combined to coach for 35 seasons after their most recent division title. It doesn’t take an abacus to calculate that is an average of just over two seasons. Ten of the 17 coaches lasted one season or less with Les Miles and Jackie Sherrill surviving the longest (five seasons) after their last division title. When we remove the coaches who left voluntarily or for reasons other than performance, the numbers look a little better. Those eleven coaches lasted a total of 26 seasons with five lasting one season or less.

Examining the SEC in a vacuum allows us to gleam a little information, but a comparison is what we really want. Are SEC coaches on a much shorter leash? To answer that, we need to look at the other Power Five conferences. The SEC had a decade or more head start on every other major conference except the Big 12, and the Big 12 ended divisional play eight seasons ago, so I have decided to lump the other four conferences together. Once again, I have included all division title winning coaches while highlighting those that were fired or forced out for performance-based reasons.

Overall, coaches in other conferences lasted longer. These 24 coaches remained employed a combined 58 years after their most recent division title. This is roughly 2.4 seasons versus 2.1 for SEC coaches. In addition, ten of those 24 coaches lasted one season or fewer. Recall this is equal to the number of short-tenured coaches from the SEC albeit with a much higher denominator. Once we remove those coaches who were not fired for performance, the numbers get better. Those 13 fired coaches lasted a total of 36 seasons which is 2.8 seasons on average versus 2.4 for fired SEC coaches and less than a quarter of the fired coaches (four of 13) lasted one season or less.

It does appear life is tougher for coaches in the SEC, at least in regards to longevity. Winning a division title doesn’t buy you a lot of time. Of course, the compensation, on par with the GDP of some Central American countries and the guaranteed contracts that are the envy of NBA players helps keep the fired coaches above the poverty line.

So we know what each team achieved, but how did they perform? To answer that, here are the Yards Per Play (YPP), Yards Per Play Allowed (YPA) and Net Yards Per Play (Net) numbers for each SEC team. This includes conference play only, championship game excluded. The teams are sorted by division by Net YPP with conference rank in parentheses.

College football teams play either eight or nine conference games. Consequently, their record in such a small sample may not be indicative of their quality of play. A few fortuitous bounces here or there can be the difference between another ho-hum campaign or a special season. Randomness and other factors outside of our perception play a role in determining the standings. It would be fantastic if college football teams played 100 or even 1000 games. Then we could have a better idea about which teams were really the best. Alas, players would miss too much class time, their bodies would be battered beyond recognition, and I would never leave the couch. As it is, we have to make do with the handful of games teams do play. In those games, we can learn a lot from a team’s YPP. Since 2005, I have collected YPP data for every conference. I use conference games only because teams play such divergent non-conference schedules and the teams within a conference tend to be of similar quality. By running a regression analysis between a team’s Net YPP (the difference between their Yards Per Play and Yards Per Play Allowed) and their conference winning percentage, we can see if Net YPP is a decent predictor of a team’s record. Spoiler alert. It is. For the statistically inclined, the correlation coefficient between a team’s Net YPP in conference play and their conference record is around .66. Since Net YPP is a solid predictor of a team’s conference record, we can use it to identify which teams had a significant disparity between their conference record as predicted by Net YPP and their actual conference record. I used a difference of .200 between predicted and actual winning percentage as the threshold for ‘significant’. Why .200? It is a little arbitrary, but .200 corresponds to a difference of 1.6 games over an eight game conference schedule and 1.8 games over a nine game one. Over or under-performing by more than a game and a half in a small sample seems significant to me. In the 2017 season, which teams in the SEC met this threshold? Here are SEC teams sorted by performance over what would be expected from their Net YPP numbers.

No SEC teams significantly over or under-performed relative to their expected record based on YPP. The top three teams dominated the conference, finishing a combined 21-3 with Auburn’s loss to LSU the only one coming against the other eleven. There is really nothing interesting or new to report in that regard. So, instead I’ll focus on something that is rather interesting.

When Jim McElwain was relieved of his duties in late October, I realized no current coach in the SEC East at that point had ever won the division! In fact, the last three head coaches to win the division (McElwain, Pinkel, and Richt) had all departed within three seasons of winning the division! Is this standard practice in the SEC? To find out, I looked at all SEC coaches that have won division titles since the league expanded in 1992. I then calculated how many seasons they coached at their school after their most recent title. For example, Steve Spurrier won pretty much every SEC East title in the 90’s at Florida, but his most recent title with the Gators came in 2000. He coached just one additional season at Florida before resigning to become head coach of the Washington Redskins. Obviously, Spurrier was not forced out at Florida, but I still wanted to get an idea of how long each coach lasted after their last division title. I rounded partial seasons up, so Jim McElwain gets credit for one full season and Les Miles get credit for five even though they did not finish out their final campaigns. The following table lists the SEC division winning coaches who are no longer employed by the schools where they won titles. I have highlighted coaches who were removed for performance based reasons to differentiate those from coaches who moved on voluntarily. We can quibble with a few of those distinctions, but for the most part, I think they are accurate.

Those 17 head coaches combined to coach for 35 seasons after their most recent division title. It doesn’t take an abacus to calculate that is an average of just over two seasons. Ten of the 17 coaches lasted one season or less with Les Miles and Jackie Sherrill surviving the longest (five seasons) after their last division title. When we remove the coaches who left voluntarily or for reasons other than performance, the numbers look a little better. Those eleven coaches lasted a total of 26 seasons with five lasting one season or less.

Examining the SEC in a vacuum allows us to gleam a little information, but a comparison is what we really want. Are SEC coaches on a much shorter leash? To answer that, we need to look at the other Power Five conferences. The SEC had a decade or more head start on every other major conference except the Big 12, and the Big 12 ended divisional play eight seasons ago, so I have decided to lump the other four conferences together. Once again, I have included all division title winning coaches while highlighting those that were fired or forced out for performance-based reasons.

Overall, coaches in other conferences lasted longer. These 24 coaches remained employed a combined 58 years after their most recent division title. This is roughly 2.4 seasons versus 2.1 for SEC coaches. In addition, ten of those 24 coaches lasted one season or fewer. Recall this is equal to the number of short-tenured coaches from the SEC albeit with a much higher denominator. Once we remove those coaches who were not fired for performance, the numbers get better. Those 13 fired coaches lasted a total of 36 seasons which is 2.8 seasons on average versus 2.4 for fired SEC coaches and less than a quarter of the fired coaches (four of 13) lasted one season or less.

It does appear life is tougher for coaches in the SEC, at least in regards to longevity. Winning a division title doesn’t buy you a lot of time. Of course, the compensation, on par with the GDP of some Central American countries and the guaranteed contracts that are the envy of NBA players helps keep the fired coaches above the poverty line.

Thursday, May 03, 2018

2017 Adjusted Pythagorean Record: Pac-12

Last week, we looked at how Pac-12 teams fared in terms of yards per play. This week, we turn our attention to how the season played out in terms of the Adjusted Pythagorean Record, or APR. For an in-depth look at APR, click here. If you didn’t feel like clicking, here is the Reader’s Digest version. APR looks at how well a team scores and prevents touchdowns. Non-offensive touchdowns, field goals, extra points, and safeties are excluded. The ratio of offensive touchdowns to touchdowns allowed is converted into a winning percentage. Pretty simple actually.

Once again, here are the 2017 Pac-12 standings.

And here are the APR standings sorted by division with conference rank in offensive touchdowns, touchdowns allowed, and APR in parentheses. This includes conference games only, with the championship game excluded.

Finally, Pac-12 teams are sorted by the difference between their actual number of wins and their expected number of wins according to APR.

Stanford and Utah were the only Pac-12 teams that saw their actual record differ significantly from their APR. Stanford over-performed relative to their APR and we went over a few reasons for this last week. Meanwhile, Utah under-performed relative to their APR. The Utes finished 1-4 in one-score conference games, losing three times (to the best three teams in the conference no less) by three points or less.

In 2016, Oregon endured their first losing season since 2004 and just their second since 1993. Their response was swift and probably justified. They fired Mark Helfrich and hired former Western Kentucky and South Florida coach Willie Taggart to take his place. Despite quarterback injuries, the Ducks won seven games in Taggart's first season. Unfortunately, a bigger job came open and Taggart left for Florida State after just one season in Eugene. Since 2005, eight other coaches have stayed at an FBS program for one season before leaving for another FBS program. How have those jilted teams fared the following season? Glad you asked.

Lane Kiffin is probably the example that most easily springs to mind, but it has occurred more frequently than you might think. Overall, no team improved following the departure of their coach and in the aggregate, the eight teams declined by about 1.4 games in the regular season. This makes sense. Having three different coaches (and likely three different systems) in three seasons would seem to be a difficult transition in a sport with as many moving pieces as football. And of course, there is the recruiting angle. Having a coach take over late in the process in back-to-back years is not the ideal way to attract incoming talent. So, it seems a little regression, or at best, no progression might be in store for Oregon in 2018. Of course, the Oregon optimist could point out (accurately I might add) that the majority of these schools were Group of Five/non-BCS programs. Tennessee and Pitt were the only Power Five/BCS programs to lose their head coach after one season. And those teams collectively declined by one game the next season. A sample size of two is not a good tool for making bold proclamations, but the odds are against Oregon making significant strides in 2018. However, even if the Ducks decline slightly or merely maintain their current trajectory, let's not be too hasty in judging the hiring of Mario Cristobal.

And what about the other side of things? How do the teams perform that snap up the one-year coach?

Those eight coaches improved their new teams on average by more than two games the next season. The only two teams that did not improve were Southern Cal with Kiffin and Louisville with Bobby Petrino. Those are understandable, as Southern Cal was hit by sanctions thanks to the rampant cheating that occurred under Pete Carroll and Louisville had just lost one of the best quarterbacks in school history (up to that point) and was moving from the AAC to the ACC. Barring the return of Jeff Bowden as offensive coordinator, it would be very shocking if Willie Taggart does not lead Florida State to more than six wins in 2018.

Once again, here are the 2017 Pac-12 standings.

And here are the APR standings sorted by division with conference rank in offensive touchdowns, touchdowns allowed, and APR in parentheses. This includes conference games only, with the championship game excluded.

Finally, Pac-12 teams are sorted by the difference between their actual number of wins and their expected number of wins according to APR.

Stanford and Utah were the only Pac-12 teams that saw their actual record differ significantly from their APR. Stanford over-performed relative to their APR and we went over a few reasons for this last week. Meanwhile, Utah under-performed relative to their APR. The Utes finished 1-4 in one-score conference games, losing three times (to the best three teams in the conference no less) by three points or less.

In 2016, Oregon endured their first losing season since 2004 and just their second since 1993. Their response was swift and probably justified. They fired Mark Helfrich and hired former Western Kentucky and South Florida coach Willie Taggart to take his place. Despite quarterback injuries, the Ducks won seven games in Taggart's first season. Unfortunately, a bigger job came open and Taggart left for Florida State after just one season in Eugene. Since 2005, eight other coaches have stayed at an FBS program for one season before leaving for another FBS program. How have those jilted teams fared the following season? Glad you asked.

Lane Kiffin is probably the example that most easily springs to mind, but it has occurred more frequently than you might think. Overall, no team improved following the departure of their coach and in the aggregate, the eight teams declined by about 1.4 games in the regular season. This makes sense. Having three different coaches (and likely three different systems) in three seasons would seem to be a difficult transition in a sport with as many moving pieces as football. And of course, there is the recruiting angle. Having a coach take over late in the process in back-to-back years is not the ideal way to attract incoming talent. So, it seems a little regression, or at best, no progression might be in store for Oregon in 2018. Of course, the Oregon optimist could point out (accurately I might add) that the majority of these schools were Group of Five/non-BCS programs. Tennessee and Pitt were the only Power Five/BCS programs to lose their head coach after one season. And those teams collectively declined by one game the next season. A sample size of two is not a good tool for making bold proclamations, but the odds are against Oregon making significant strides in 2018. However, even if the Ducks decline slightly or merely maintain their current trajectory, let's not be too hasty in judging the hiring of Mario Cristobal.

And what about the other side of things? How do the teams perform that snap up the one-year coach?

Those eight coaches improved their new teams on average by more than two games the next season. The only two teams that did not improve were Southern Cal with Kiffin and Louisville with Bobby Petrino. Those are understandable, as Southern Cal was hit by sanctions thanks to the rampant cheating that occurred under Pete Carroll and Louisville had just lost one of the best quarterbacks in school history (up to that point) and was moving from the AAC to the ACC. Barring the return of Jeff Bowden as offensive coordinator, it would be very shocking if Willie Taggart does not lead Florida State to more than six wins in 2018.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)